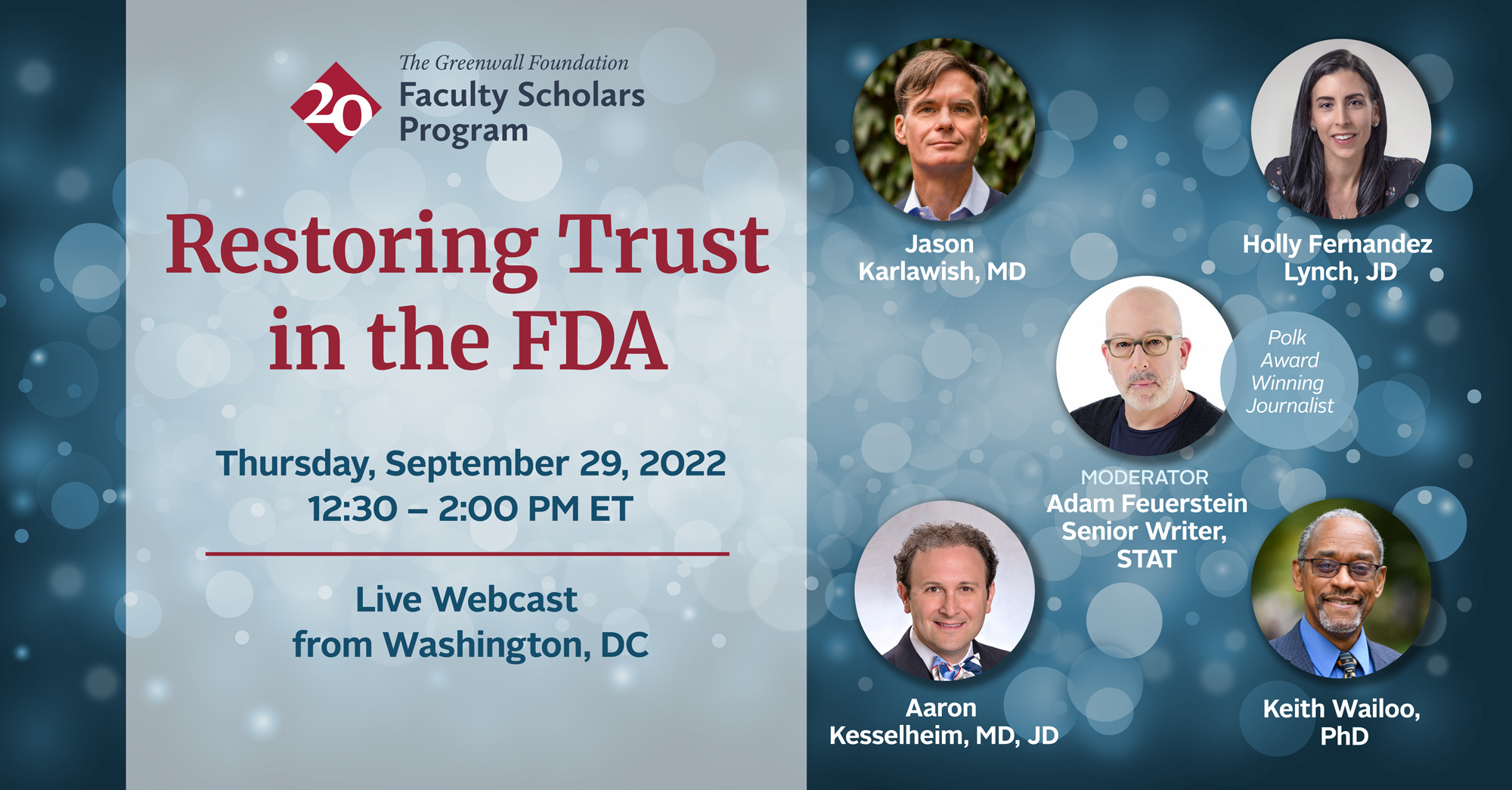

In September, The

Greenwall Foundation hosted a panel

discussion about the state of public trust in the FDA. The participants, which included four members of the Greenwall Faculty Scholars Program community and moderator, journalist Adam Feuerstein, discussed whether and how trust has been lost in the agency, and how it might be won back.

Greenwall Faculty Scholars

and Alums in the audience weighed in with their takes on the discussion on Twitter and here

on our blog. We share some of their reactions below.

Matthew McCoy, PhD

How should FDA interact with patients?

During the panel, Dr. Karlawish raised a critical

question: “How should FDA interact with patients?” Few would dispute that

there’s a role for patient voice in the drug approval process. Patients and

caregivers can offer firsthand accounts of what it’s like to live with a

particular condition and what sorts of treatment options they would value. But

what FDA sometimes refers to as the “patient perspective” is never monolithic.

Different patients have different experiences, different challenges, and

different priorities. It’s therefore important to reflect on how and from whom

FDA solicits patient input. As Dr. Karlawish noted, FDA has issued thoughtful

guidance on collecting representative patient experience data. But many

opportunities for patients to share perspectives directly with the FDA—such as

open public hearings at advisory committee meetings—continue to favor organized

and energized advocates whose views may not reflect those of broader patient

communities. As FDA aims to increase opportunities for patient engagement with

the agency, it should take measures to ensure that it’s capturing a range of patient

perspectives and not being overly reliant on forums that privilege the loudest

voices in the room.

As the panelists rightly noted, FDA

confronts a real challenge when incorporating the patient voice into the drug

approval process generally and into accelerated approval particularly.

Patients with serious diseases who lack meaningful treatment options feel

desperate. And so, it is reasonable that many of them would be willing to

make the tradeoff at the heart of accelerated approval: to sacrifice some

certainty for greater speed.

I would, however, suggest that

there are multiple problems with using patient desperation to justify

acceleration (i.e., accelerated approval). Here are three: (1) Patients

with any given condition are not a monolith despite having the same diagnosis;

for example, some might want to devote resources to care rather than directing

resources to an uncertain, sometimes very expensive, drug while we wait for

results from post-approval trials. FDA needs to better account for these

varied perspectives. (2) The interests of current patients do not

necessarily align with those of future patients who will one day be affected by

the same condition, and FDA has not yet adequately determined how to weigh

future patients’ interests. (3) Listening to patients may not be

enough. The broader public has an interest in the precedents set by

accelerated approval, particularly if an accelerated approval decision will

have follow-on effects for insurance costs (see, e.g., how aducanumab affected

Medicare premiums) or on the level of evidence that suffices for other approval

decisions.

I’ve had the chance to write about

these issues with other Greenwall faculty scholars in the aftermath of

aducanumab’s accelerated approval, and I look forward to continuing to think

about the ethical and policy dimensions.

You can watch watch the panel in its entirety here:

Lori Freedman, PhD

Lori Freedman, PhD